WHILE NEWS coming out of Egypt, Syria and Turkey of late has been decidedly disturbing, the situation in Iran, putative member of the Axis of Evil, has been rosier. Predictions prior to the Iranian presidential election of June 14 were dire. Remembering what happened four years ago, where a disputed electoral result saw the political situation deteriorating, few held high hopes for this latest election.

Pre-electoral hijinks were at their usual level in Tehran, with the Guardian Council banning several significant candidates from running, theoretically paving the way for a hardliner to win, an outcome that pundits expected would tighten the conservative grip on the levers of power and further alienate the populace from the regime. In the event, Hassan Rouhani, running on a pro-reform ticket, won the election. His victory prompted widespread jubilation across Iran.

It remains to be seen if such a result is a sleight of hand from the regime, if it’s a sign of pragmatism on the part of those hardliners who wield. Or it may be that regime insiders wedged themselves.

It remains to be seen if such a result is a sleight of hand from the regime, if it’s a sign of pragmatism on the part of those hardliners who wield. Or it may be that regime insiders wedged themselves.

Did the regime realise that it needed to concede some ground to a largely disengaged electorate and offer up a presidential candidate who, while remaining an insider, could address societal ills and salve the political frustrations of Iranians at large? Or did an attempt to eliminate pro-reform voices from the electoral rolls mean that the hardline vote was split amongst a range of conservative candidates thus leaving the way clear for all voters of a reformist inclination to vote for the single palatable candidate? Whatever the case, the punters opted for Rouhani, giving him a resounding majority.

While there has been some cynicism about the installation of Rouhani (could he just be a Khamenei stooge?), the fact is that suddenly the political situation in Iran and the geopolitical scene around it seem a whole lot less ominous. Rouhani appears to have the ear of the Supreme Leader and the support of the people, meaning that real change may be a possibility, perhaps. (Yes, that is a qualified observation!) There have been plenty of “springs” forecast in the region in recent years, most of which have been beset by squalls and which have failed to deliver real change, but could it be that an “Iranian spring” is in the offing?

As reported in The Guardian after the inauguration of the new president, Rouhani signalled his intention to engage with the West, and the US in particular, in order to redress the poisonous and combative atmosphere that has long persisted but which had reached a peak under the previous incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

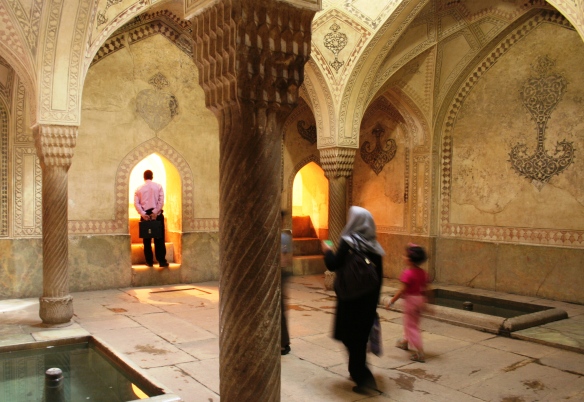

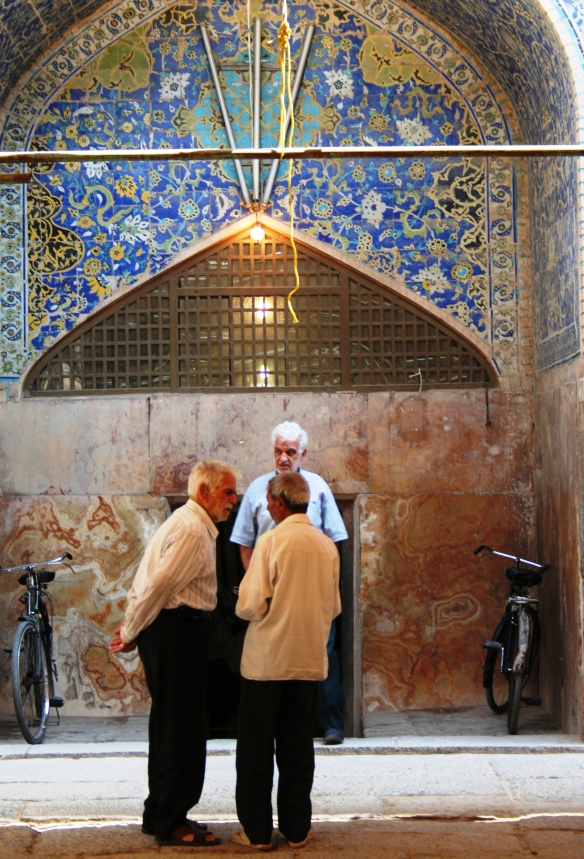

It’s tempting to believe that Rouhani’s campaign promise to re-orient dealings with the West was a significant part of his appeal to the Iranian electorate. In my own experience, most Iranians-on-the-street harbour no ill feelings towards the West or Westerners (with some exceptions, no doubt). Generally they are eager to engage and many speak very good English. The welcome Western travellers receive in Iran is genuine and spontaneous, even more so than in Turkey, in my estimation. Indeed, some pundits say that of all Muslim nations it is the Iranians (hardline elements aside) who are most enamoured of the US and the West in general.

It’s tempting to believe that Rouhani’s campaign promise to re-orient dealings with the West was a significant part of his appeal to the Iranian electorate. In my own experience, most Iranians-on-the-street harbour no ill feelings towards the West or Westerners (with some exceptions, no doubt). Generally they are eager to engage and many speak very good English. The welcome Western travellers receive in Iran is genuine and spontaneous, even more so than in Turkey, in my estimation. Indeed, some pundits say that of all Muslim nations it is the Iranians (hardline elements aside) who are most enamoured of the US and the West in general.

Another significant part of Rouhani’s appeal to Iranian voters was his pledge to focus on economic issues. The Iranian economy had gone seriously pear-shaped during Ahmadinejad’s tenure, despite windfall oil royalties that should have guaranteed a healthy economic outlook. Ahmadinejad’s bombast and sabre-rattling have clearly done Iran little good, in particular his intransigence on the nuclear issue, which, in providing the impetus for economic sanctions, has only worsened the impacts of his erratic, ill-judged and populist economic policies.

Newly incumbent Iranian presidents have made brave statements before; such bravado has led to their undoing, or at least their falling in the estimation of Iranian voters when said pledges, however basic, fundamentally sound or eminently sensible, prove undoable in the prevailing political climate. Such failure, or inability, to follow through results in the disillusionment of the Iranian electorate. (Think of Khatami’s brandishing of a copy the constitution on the campaign trail in 1997 and swearing that it was his intention, if elected to the presidency, to uphold the rule of law inherent within the constitution. Hardline stonewalling and general chicanery stymied his reform programme and saw him in the end derided as a “lame duck” president.)

Bringing a degree of accountability to the Iranian political arena, the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto has instituted the Rouhani-meter, a gauge to see how well Rouhani goes in pursuing and implementing his campaign promises. The meter is touted as a mechanism to “enhance the profile of democratic voices outside Iran, to connect them to Iranians inside Iran, and provide a space for public dialogue”. It certainly demonstrates that Rouhani ran on an ambitious platform, but let’s hope that in months and years to come it doesn’t serve to highlight the hopelessness of the reformist cause in Iran. Rouhani must pull of a delicate balancing act, in retaining the support of the electorate while (and more importantly) not incurring the wrath or invoking the resistance of the hardline conservative apparatus that determines the trajectory that the Islamic Republic is allowed to travel in.

While Iranians are no doubt expecting Rouhani to follow through on his campaign platform any optimism is tempered by bitter experience following both the Khatami era false dawn and the forceful suppression of the Green movement after the elections of 2009. The prospect of real change in the Iranian political sphere remains difficult to gauge.

On other fronts, there have been some positives since Rouhani’s inauguration in August. The appointment of Mohammad Javad Zarif as Foreign Minister was generally well received. US-educated and with a track record of pragmatic and even-handed diplomacy, Zarif marked a different course for Iranian international relations when he conveyed his best wishes for the Jewish New Year.

On other fronts, there have been some positives since Rouhani’s inauguration in August. The appointment of Mohammad Javad Zarif as Foreign Minister was generally well received. US-educated and with a track record of pragmatic and even-handed diplomacy, Zarif marked a different course for Iranian international relations when he conveyed his best wishes for the Jewish New Year.

The Supreme Leader, Khamenei has since given hints that Iranian positions may not be so forcefully held, remarking that in diplomacy “heroic flexibility” was sometimes desirable. Such a position led to speculation that there may have been an opening for a one-on-one meeting between Barack Obama and Rouhani last week at the UN general assembly. This idea was eventually scotched, presumably because hardliners both in US and Iranian camps would have kicked up too much of a fuss. In the end, contact was made by phone, a conversation that by all accounts proceeded smoothly. It was a small but significant step, and hopefully a prelude to further engagement.

In an indication of the struggle that Rouhani faces to maintain a balance between engaging with the West and incurring the wrath of hardline regime loyalists in Iran, he was met by a significant crowd in Tehran upon his return from talking at the UN. Some threw eggs and shoes at him, others welcomed him warmly. However it appears that the majority of Iranians are excited at the prospect of a thaw in Iran-US relations.

Is a thaw a harbinger of a spring? Let’s hope so.