So they pushed the clocks forward an hour, marking the end of summer, the changing of the season. In Diyarbakır darkness descends early now, and abruptly. We are some 1000km southeast of İstanbul, as the crow flies, but still in the same time zone. By five o’clock the gloaming (such an apt word, promising so much, somewhere between ‘glow’ and ‘looming’) is all but passed and the street lights flicker on.

So they pushed the clocks forward an hour, marking the end of summer, the changing of the season. In Diyarbakır darkness descends early now, and abruptly. We are some 1000km southeast of İstanbul, as the crow flies, but still in the same time zone. By five o’clock the gloaming (such an apt word, promising so much, somewhere between ‘glow’ and ‘looming’) is all but passed and the street lights flicker on.

It strikes me that at twilight you can see cities at their most candid. Not that the cities of southeastern Anatolia maintain any pretensions or artifice. But in the failing light, as people close up shops, or make their way home, or farewell workmates, or make a last dash to pick up necessities for the evening meal, life is revealed in all of its gritty, mundane, workaday magnificence. Shadows loom, cries seem to hover in the air. If you look up at the right time, a swallow zips overhead.

Clockwise as in a Buddhist pilgrimage, I continue a vague circuit within Diyarbakır’s city walls, an on-again off-again ramble, over several days, that has succumbed to diversions, zigzags, backtracks and unplanned stops. These are the second-longest land walls on earth, after the Chinese Wall. Mighty, in ominous black basalt, they bear the imprints and flourishes of dynasties, empires, fly-by-night warlords who have rumbled through this frontier territory where spheres of Persian, Arab and Turkish influence overlap like a Venn diagram. A litany of dynasties to fire the imagination, if you are given to such things: Seljuk, Ayyubid, Safavid, Artuklu, Karakoyunlu, Akkoyunlu. Seems everybody but the Ottomans.

Climbing the steps to Keçi Burcu, a robust tower near the southernmost point of the walls. Inevitably, on the parapet, there is an open-air tea salon. Wooden banquettes against stone walls, and tables with knee-high stools. Locals gather for çay, for countless infernal cigarettes, to chatter and take selfies, while ignoring the view as darkness descends. One young guy sits cross-legged on the battlements, as if he is sentinel over all of Mesopotamia. Below, the Tigris snakes southward.

Climbing the steps to Keçi Burcu, a robust tower near the southernmost point of the walls. Inevitably, on the parapet, there is an open-air tea salon. Wooden banquettes against stone walls, and tables with knee-high stools. Locals gather for çay, for countless infernal cigarettes, to chatter and take selfies, while ignoring the view as darkness descends. One young guy sits cross-legged on the battlements, as if he is sentinel over all of Mesopotamia. Below, the Tigris snakes southward.

I descend again, passing Mardin Kapısı, the southern-facing of the city’s four main gates. Further on there is a large fissure in the walls. Outside are sprawling suburbs of cheap, concrete apartment blocks and gecekondu houses. Overhead power lines, rubble-strewn, dusty kerbs. Voices carry on the breeze, snatches of song, a radio broadcast, a dog barks. Even these neighbourhoods, under an eye-shadow-blue swirl of sky and cloud, stippled with pools of orange street light, seem somehow homely, welcome, beckoning at this hour. (Perhaps I’ve been away too long.)

As I reach Urfa Kapısı, the western-facing gate, above a roadside watermelon stall a sickle moon rises, the most perfect of clichés, as if someone has sunk a fingernail into the velvet expanse of sky to let in a crescent of yellow light.

Back inside the walls, passing traffic raises dust and puffs of exhaust, and throws beams of light across shopfronts, trees, the city walls, like search lights perennially seeking out some elusive target. At the centre of town where the east-west and north-south routes cross, dolmuşes gather passengers, everyone headed home, burdened with packages, plastic bags, tubs of produce. And as each vehicle roars off I experience that fleeting shudder of exhilaration that I used to feel as a backpacker. An understated euphoria, a butterfly in the stomach, at the beginning of each new journey, at the anticipation, the what-comes-next that each departure promises.

Another evening, at the Meryemana Church, a Syrian Orthodox church that has stood here, in various incarnations, for nigh-on 1800 years. A flight of pigeons swoops above the belfry. (Shouldn’t that be bats?) By chance, I am here in time for evening prayers, Vespers (another redolent word). I am invited to stay. ‘You can sit,’ the priest, a man who somehow embodies resilience, with a black beard and white prayer cap, tells me.

Another evening, at the Meryemana Church, a Syrian Orthodox church that has stood here, in various incarnations, for nigh-on 1800 years. A flight of pigeons swoops above the belfry. (Shouldn’t that be bats?) By chance, I am here in time for evening prayers, Vespers (another redolent word). I am invited to stay. ‘You can sit,’ the priest, a man who somehow embodies resilience, with a black beard and white prayer cap, tells me.

It’s a small congregation, just the priest, his two children, his wife, a single older parishioner. And me, observing. Prayer is informal, slightly chaotic, not unlike Islamic ritual in its casual aspect. The priest’s genuflections and prostrations resemble nothing so much as Islamic salat, but for the fact that he crosses himself as he rises from each prostration. He then pulls back a curtain to reveal the altar, a sumptuous recess of velvet, electric candles, gilt and almost-baroque ornamentation, all topped with muqarna that would not look out of place in the Alhambra in Granada.

The children chant from the Bible (in Aramaic, the ‘language of Jesus’, as I am later told), as the priest struggles to light a taper with an oven lighter, repeatedly firing the trigger until a shot of blue flame emerges. He then lights a censer, which his son takes and approaches the altar, while continuing his chanting, proceeding to swing it and send clouds of fragrant incense heavenward.

Observing all of this, I can see the seductiveness of faith, the comfort and reliability of ritual as a crutch in the every day, although it must be said that the chanting had an air of going-through-the-motions. At prayer’s end the priest teaches me my first word of Aramaic: ‘towdi’. Thankyou. And I depart into the evening.

Later, in a backstreet, in the darkness, a woman in baggy şalvar and headscarf fans a fire in a cobbled alley, placing torn pieces of cardboard on to her fire, over which she is roasting narrow purple aubergines.

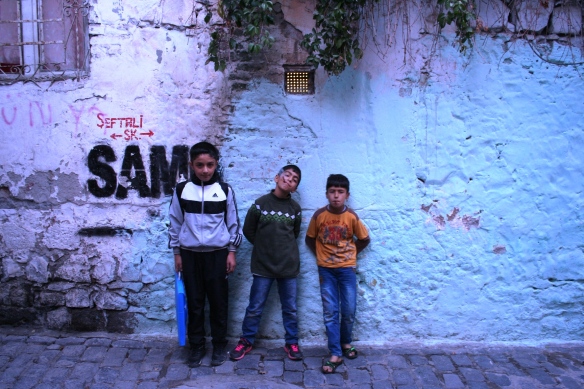

The next afternoon, to see Yeni Kapı, the eastern-facing gate, the only one I haven’t visited. This is a poor part of town. I am warned by a local about thieves, as I have been repeatedly all over town. I never encounter anyone who appears even slightly inclined towards theft. Here the stuccoed walls of humble homes are painted burgundy, puce, pastels in unlikely, exuberant combination, in contrast to the dour black granite of the city walls and the grand konaks, stately homes with alternating black and white striped door and window arches. From Yeni Kapı I look out over the Hevsel gardens, green plots on the flood plain of the Tigris.

In Mar Petyun, Chaldean Catholic Church of St Anthony. I had visited here in 1992. Then it was sombre and dilapidated. Now the lights are ablaze, all appears refurbished. An air of rejuvenation. A sign says photography is not allowed, but some locals come in and immediately take selfies, so I too pull out my camera, which I hadn’t done at Meryemana.

In Mar Petyun, Chaldean Catholic Church of St Anthony. I had visited here in 1992. Then it was sombre and dilapidated. Now the lights are ablaze, all appears refurbished. An air of rejuvenation. A sign says photography is not allowed, but some locals come in and immediately take selfies, so I too pull out my camera, which I hadn’t done at Meryemana.

On my last night in town, a Kurdish wedding. Hearing, rather than finding it. Drum kit, saz and davul. Amps on 11. Feedback roaring. The drumbeat is so loud I can feel it in the pulse in my throat. On a concrete floor, under a tin roof decorated with coloured fairy lights, this isn’t steam punk. Perhaps dust punk.

The saz rages in wiry, sinuous lines and trills, climbing and crescendoing, occasionally plummeting to sound a fat whoomp. The saz, drum kit and davul, move in different rhythms and sequences, but coming together to mark the end of each stanza with a clattering, clamorous full stop. Boom ka-ka ka-boom!

I can detect no sign of a bride or groom. Seated along the walls are older men, sipping tea. On another side, on knee-high stools, women wearing coloured headscarves are massed, watching. Like coloured birds roosting.

The centre of attention is the young men, dancing, arms linked, in line. Slim youths, sweaty and raucous, in jeans and long-sleeved shirts. A red tinsel tassel is handed around, giving the bearer permission to break from the line and free form. Each takes their turn in a flurry of jaggedy movements, all bending knees and pointy elbows, shoulders swaying and skittish feet stamping.

The centre of attention is the young men, dancing, arms linked, in line. Slim youths, sweaty and raucous, in jeans and long-sleeved shirts. A red tinsel tassel is handed around, giving the bearer permission to break from the line and free form. Each takes their turn in a flurry of jaggedy movements, all bending knees and pointy elbows, shoulders swaying and skittish feet stamping.

The scene strikes me as an outpouring of joy. Of communality. Of shared intent. Some sort of release. I can’t say if it’s appropriate or symbolic, or if it’s just plain poetic. But I am ending my time in Diyarbakır in a blaze of music, light, adrenaline.

Ka-ka ka-BOOM.

ANOTHER YEAR ends. Hallelujah to that!

ANOTHER YEAR ends. Hallelujah to that! Skylines, cityscapes, landscapes, wondering what lies beyond the horizon. Hope.

Skylines, cityscapes, landscapes, wondering what lies beyond the horizon. Hope.